This blog has been a bit of struggle for me. My intention has always been to focus on the artwork, but my natural wordiness has always seemed to get in the way. So, from now on, I’m going to let the art do the talking, for the most part, and take you through some of the steps I’ve gone through in creating my work.

As illustration has become a even larger part of my business, I’ve really taken to digital painting. Having the ability to zoom in and take images apart really appeals to someone as detail-oriented as I am. It’s really given me the chance to push my skills beyond what I could do with just a pencil. Having the ability to erase your mistakes or start over has been a big help too.

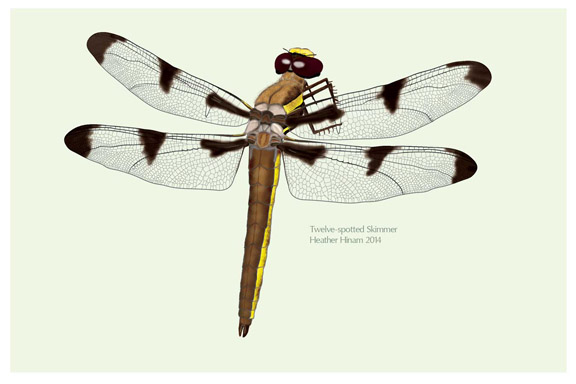

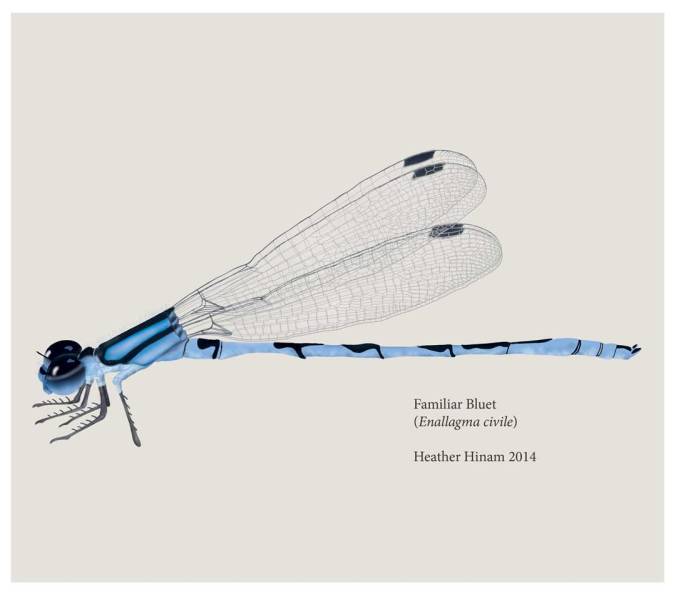

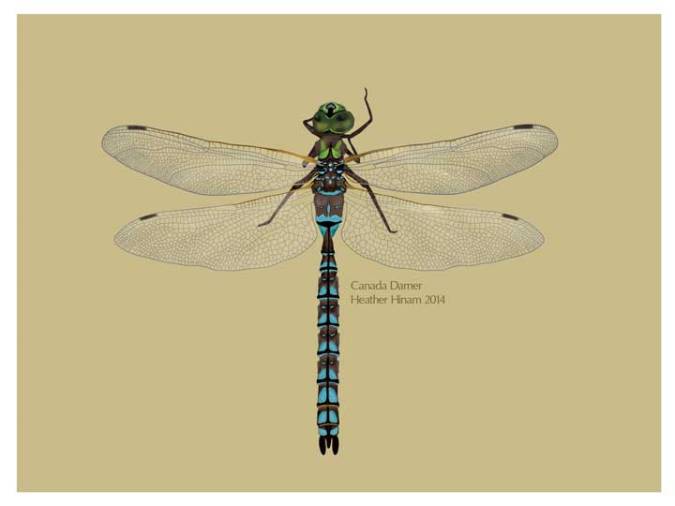

Dragonflies are an especially fun subject. They seem almost mechanical, delicate, fluttering jewels on one hand and strange, alien cyborgs on the other. Still, they’re a great subject to get your feet wet with in the world of digital painting, a great mix of eye-crossing detail and forgivingly smooth body surfaces.

Here are a few examples:

Their symmetrical shape also makes life a little bit easier. I only had to draw one pair of the wings, which considering how long the veining took, is a really good thing.

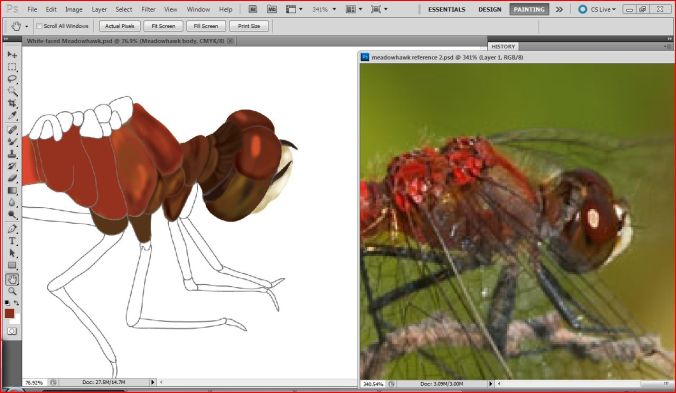

This white-faced meadowhawk posed a bit more of a challenge, though. Unlike darners and skimmers, meadowhawks tend to sit with their wings held down, around their bodies. I wanted to capture that and keep it from looking like an insect with a pin stuck through it. So, it took a bit of careful planning. Despite my new love of digital painting, everything I do still starts with a pencil and paper. In the case of the meadowhawk, though, I left the wings off and worked them completely separately to keep all the lines from getting muddled.

Despite my new love of digital painting, everything I do still starts with a pencil and paper. In the case of the meadowhawk, though, I left the wings off and worked them completely separately to keep all the lines from getting muddled.

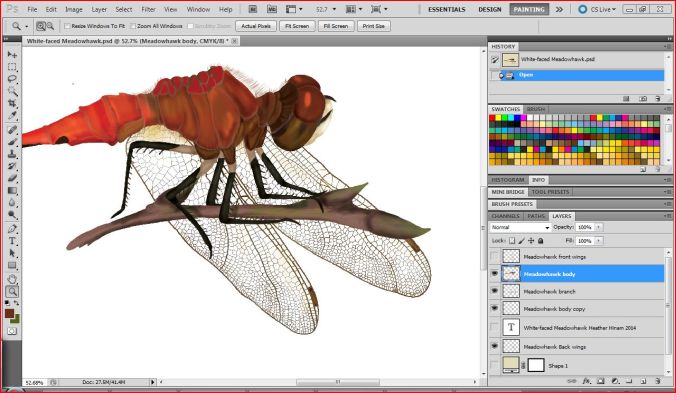

Once the drawing was scanned, the process was fairly simple. The lines were traced in Illustrator, then the image was painted in Photoshop.

Probably the handiest aspect of working an illustration like this in Photoshop, rather than trying to do it on paper, is the ability to layer your image. The meadowhawk was composed of five layers (back wings, back legs, branch, body/front legs and front wings) that I could turn on and off, allowing me to work on parts of the insect without getting distracted by the rest of it.

Put it all together an it becomes a seamless illustration. Once you get the hang of the depth of your planned image and figure out how many layers you’re going to need, just about anything is possible. Having spent a few weeks getting to know these amazing natural jewels in detail has left me in awe of the complexity and elegance that is the result of over 300 million years of evolution. Next time you see a dragonfly, take a moment to have a closer look. You will be amazed.

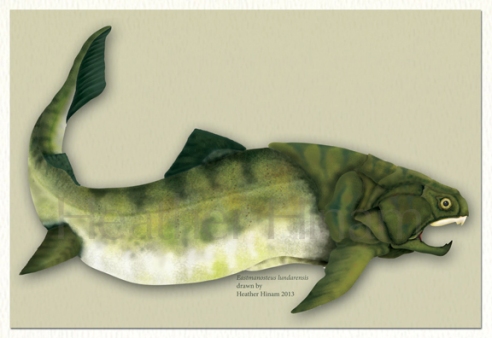

As with most other animal drawings I do, I started with the eye. Being able to block each section individually really came in handy for keeping the pupil nice and crisp. Painting in Photoshop is a lot like regular painting or coloured pencil. It’s all about layering, building up colour to create depth and shape.

As with most other animal drawings I do, I started with the eye. Being able to block each section individually really came in handy for keeping the pupil nice and crisp. Painting in Photoshop is a lot like regular painting or coloured pencil. It’s all about layering, building up colour to create depth and shape.

After the slow plodding that was the armour plates, the rest of the body was almost a breeze. A reminder that this whole thing started on paper is in the tail swish. It was the result of not having enough room on the page for the whole fish.

After the slow plodding that was the armour plates, the rest of the body was almost a breeze. A reminder that this whole thing started on paper is in the tail swish. It was the result of not having enough room on the page for the whole fish.